Case of a major release of radioactivity …

When the health and safety of an entire population is at risk following a nuclear-related accident, radioprotection has to be taken to a different dimension. What specific measures can be taken when large amounts of radioactive matter are released into the atmosphere?

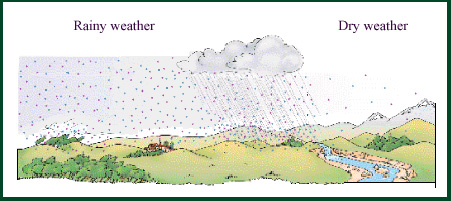

Mechanisms of radioactive fall-outs

Deposits of radioactive isotopes on the ground are sources of external exposure as well as internal exposure if they find their way into the food chain. In dry, windy weather radioactive particles may reach the ground, but it is mainly rain that accelerates deposits, forcing the particles to the ground. This explains the patches of radioactivity observed on the map of Europe shortly after Chernobyl. These patches correspond either to regions where it had been raining or regions of mountains which had stopped the radioactive cloud.

© IRSN/dessin : Martine Beugin

The ability to provide adequate protection depends on an understanding of the risks involved. The catastrophic events that occurred at the Chernobyl reactor in 1986 have taught us a tragic lesson on how to ensure the security of a population. The smaller incident at the Mayak reactor in the Urals (1957), as well as the Three Mile Island (1979) and Tokaimura (2000) accidents have also served as wake-up calls, though the latter two fortunately did not release any radioactive waste. Experience has also been accumulated from the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the nuclear bomb tests that continued throughout the 50s and 60s – though these were conducted in principle far from inhabited areas.

The threats posed immediately after a nuclear explosion or a nuclear accident depend on the elapsed time. Seconds after the event has occurred, short-lived elements predominate over a very small area near the bomb impact or the accident. Over time, the most active elements blown into the atmosphere have had time to dissipate, the longer-lived elements take over. They are less radioactive but can spread the radiation over large areas.

The main risks of exposure are posed by the radioactive cloud, the inhalation of radioisotopes in the air, and deposits of radioactive elements in the ground as well as in sources of food and water. The main worry is that the exposure humans feel will be an internal as well as an external phenomenon.

The main cause of external exposure is the gamma rays which can penetrate hundreds of meters of atmosphere before being absorbed. They originate from the radioactive cloud formed at the moment of the explosion, and can also be emitted from radioactive deposits on the ground. The internal exposure is caused by the inhalation and ingestion of active radioactive substances that vanishes in a few days or weeks after the release, primarily iodine 131 which attaches itself to the thyroid gland.

As with natural catastrophes, simple yet effective measures can prevent the more serious consequences. Possible actions range from evacuation and sheltering of populations to the careful monitoring of food and drink made available in the regions of concern.

Food controls

Food radioactiviry control after a major accident avoid internal expositions resulting from uptakes of contaminated food. The photograph shows the control of fish caught off the Japanese coasts after Fukushima. The food controls were very effective in reducing the exposure of populations.

© DR

In the case of the 2011 Fukushima accident, the four days delay between the tsunami and the main release of radioactivity allowed to provide an efficient sheltering of populations. But 210 000 people have to be evacuated. Long term contaminations remain.